Information

Sheet--Primer on the Habsburg Monarchy

Tooley

The Dual Monarchy, as Austria-Hungary was sometimes called after

1867, was in essence the last constitutional shape of the Habsburg

Empire. As such, it was this dual structure within the Empire that

impacted every aspect of state leadership right up to the end of

World War I.

Of course, the Habsburg Empire was intimately connected with the

history of Central Europe and Europe as a whole for hundreds of

years. The Habsburg family, with its seat in Vienna, ruled the

Holy Roman Empire for its last centuries, until Napoleon ended the

HRE in 1806. From the confederal, decentralized nature of the

Holy Roman Empire, and from the policies of the Habsburg family, the

dynamic of Habsburg rule tended to be the soft touch, negotiation

instead of coercion, local autonomy instead of centralized control,

marriage instead of war.

Indeed, we have to make a distinction here. The Holy Roman

Empire included almost everything that is today Germany, Austria,

Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Belgium, the Netherlands, and

Luxembourg. It also included some territories now in Italy,

France, Switzerland, Poland, Russia, and Croatia. (Have I missed

anything?) The Holy Roman Empire was held together as a

confederation of independent entities that lay along a huge

continuum, from small knightly holdings and medium-sized walled

towns to big, important states that could boast armies many tens of

thousands strong.

This is from the Schedelian "World Chronicle" produced just

before 1500. The figures are leading princes from the Holy Roman

Empire.

The Habsburg family held this position for several hundred

years--held it very adroitly, one must say. It certainly

wasn't easy. But a note here: the Habsburg Emperors were

at the same time heads of the family's "crown lands," territories

which they held individually and under various titles:

"Archduke of Styria," for example, or "King of Hungary." In fact,

acquiring much eastern real estate in the long struggle with the

Ottoman Empire, the Habsburg Empire was in part outside of (mostly

to the east of) the Holy Roman Empire, which they also

controlled. (And yes, a branch of the family was also in power

in Spain from early sixteenth century until the early eighteenth.)

A second aspect of the Habsburg's ability to hold onto the reins of

the Holy Roman Empire was its famous marriage policy. "Others

conquer," the Habsburg household adage ran, "We marry!" And indeed,

though the expansion of the Habsburg Empire was hardly bloodless, it

grew at a significantly lower cost in body count than almost all

other great European states. The Habsburgs put a very high value on

marriage partly for this reason. A great many Habsburg princes (and

princesses) prided themselves on their family's ability to lessen

conflict by marrying into other ruling dynasties. Indeed, many

of the greatest Habsburg rulers were convinced that not only

marriage, but also negotiation with elites and regions, was far

better than military force. This is certainly an important

theme to think about, since the "new" world of hard-edged

nationalist states in the nineteenth century were little amenable to

such peace-producing strategies.

Back to the Holy Roman Empire as a whole, it will perhaps be a

surprise to find out that there were well over a thousand

independent "countries" or states in this confederation, and even if

some of the marginally independent categories are excluded, there

were still nearly 350 independent states. The role of the

Emperor was to keep an eye on the whole thing, but no one ever

imagined that all of the Empire "belonged" to the

Emperor. Each unit guarded its autonomy fiercely.

But there is more. The Emperor's position was not hereditary,

but elective. Yes, you heard that right. Elective.

Now, the electorate was pretty small: seven (later

eight). Originally, in the tenth century, these were the heads

of large regions related to former tribe status. By the thirteenth

century, the Electors were the crowned heads of some of the leading

states of the Holy Roman Empire--well, sort of, since for good

measure one of the electoral princes was the King of Bohemia, whose

involvement was real but limited in some ways. The other electoral

states were The Prince-Bishopric of Mainz, the Prince-Bishopric of

Trier, the Prince Bishopric of Cologne, the County Palatine, the

Duchy of Saxony, and the Margavate of Brandenburg. Bavaria

would be added later, and some of these would drop out, but the

important thing is that these rich, powerful, influential heads of

states (some of them in holy orders) voted on the new Emperor at the

end of each reign.

This process meant, of course, that any ruling Emperor hoping for

his son (or in one case, his daughter) to become Emperor would have

to play nice with the Electoral states: giving them subsidies,

granting various favors, marrying off children to their royal

houses, etc.

On the other hand, within the multifaceted "constitution" of the

Empire, one of the Emperor's other important roles was to help the

smaller units of the Empire defend themselves from the aggression of

the more powerful units. The Emperor did this partly through

the Reichstag, a tripartite council representing elites

throughout Central Europe whose legislation was theoretically

binding even on the Emperor. Similarly, the Reich Court of

Chamber exercised wide-ranging jurisdiction to assist the king when

injustices among the states occurred. The Emperor could even use

these institutions to help him place a "ban" on offending

individuals or states, placing them outside the law and making them

free game for anyone to kill or expropriate. In these ways,

the Emperor used his position to coordinate the military forces of

the hundreds of less powerful states so that, collectively, they

could confront any of the powerful German states.

But all this began to crumble with important changes during the

Reformation and the Thirty Years War. That war ended with the Treaty

of Westphalia, which gave impetus to new power centers very

detrimental to the old balances and negotiation of the HRE.

And by the time Napoleon put paid to this Empire by defeating the

Austrians and Prussians and reorganizing Central Europe in 1805/6,

many of these habits of decentralization and localism had gone into

decline. Indeed, many of the smallest states simply

disappeared, folded into neighboring countries. Most of this

work was done in a single stroke by Napoleon, as he pared the Empire

down from over three hundred states to thirty-eight or

thirty-nine. These trends of centralization continued during

the period of the "Germanic Confederation," which lasted from 1814

to 1867.

Two other important trends marked this period for the Habsburg

Empire. Indeed, during this period, the old rivalry between the

Habsburgs in Vienna and the Hohenzollerns in Berlin

(Prussia/Brandenburg) reached its greatest height, spurred on by

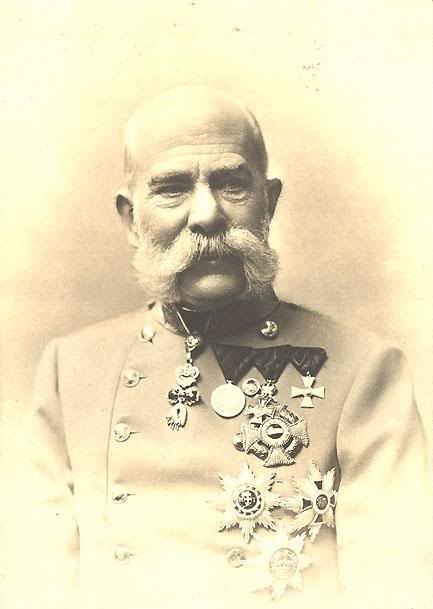

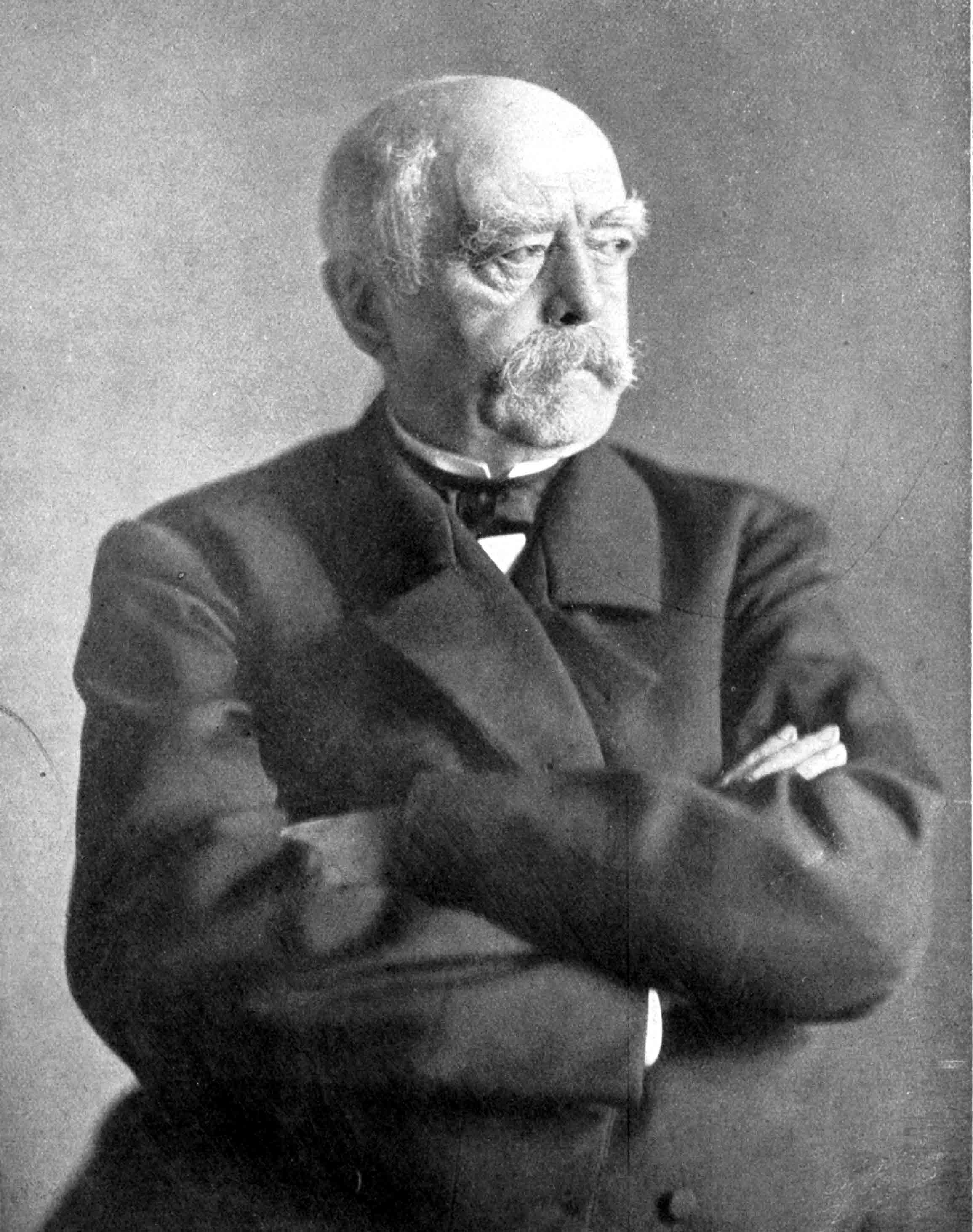

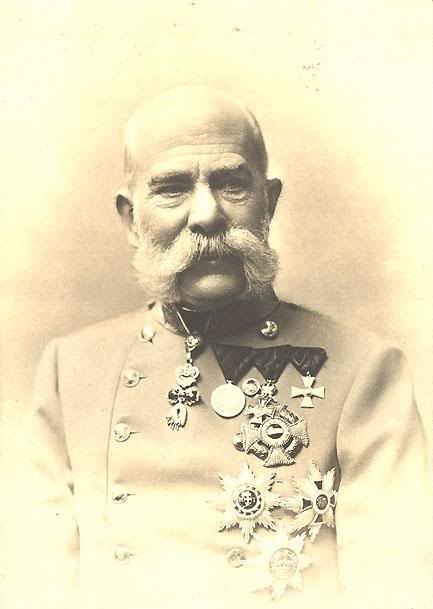

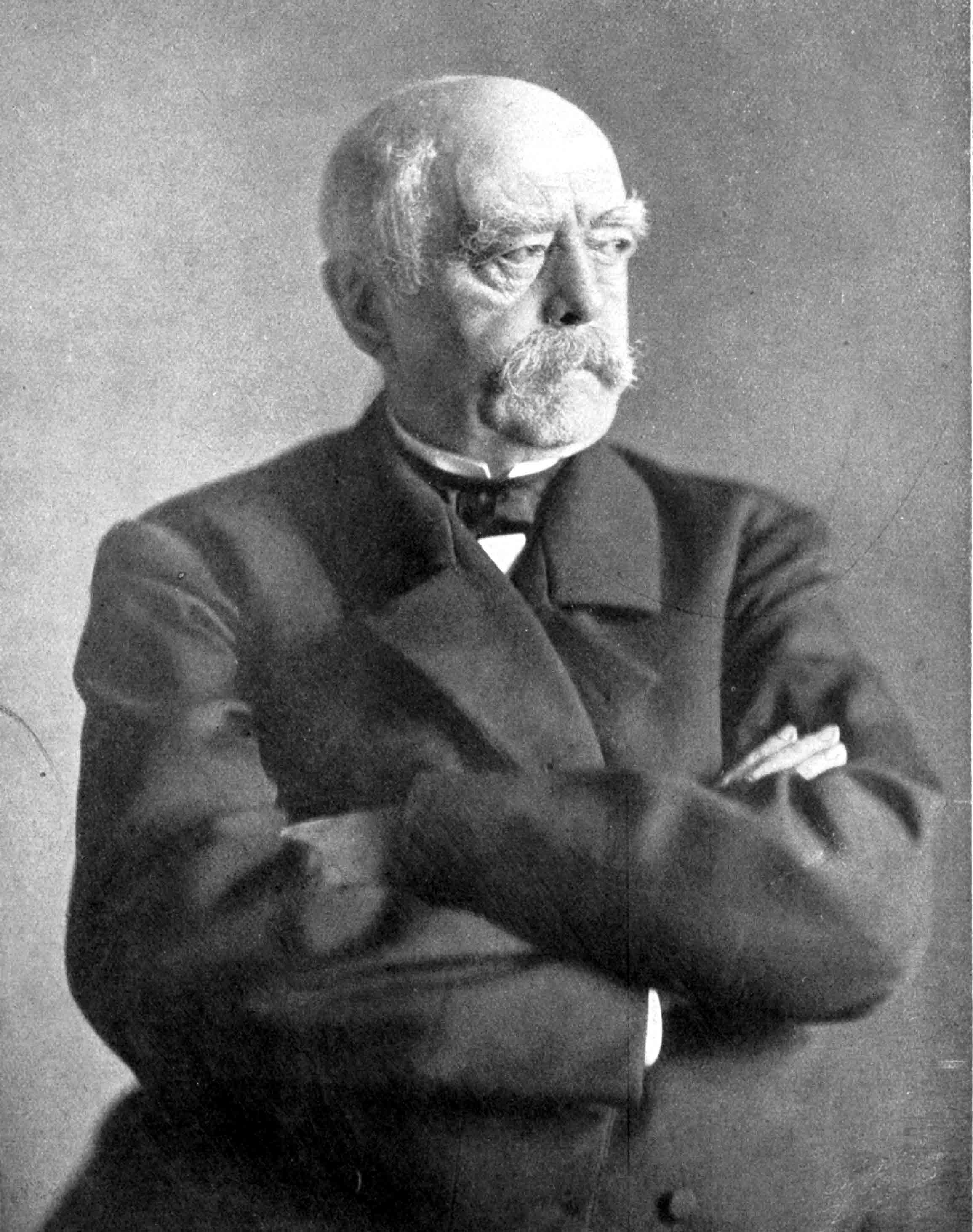

nineteenth-century nationalism. In the 1860s, Otto von

Bismarck engineered three wars which effected the final split of

"Germany" from the influence of the Habsburgs. The new "German

Empire" was founded in 1871. But defeated by the Prussians in the

Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the Austrian lands had been reorganized

to reflect the decline of the central power of Vienna. All this

happened under the watch of the long-time Habsburg Emperor, Franz

Josef (1848-1916). Henceforth, from 1867, the Habsburg "crown

lands" and their appendages were organized into two parts of the

Empire: the Hungarian part with a seat at Budapest and the

Austrian part with a seat at Vienna. The Habsburgs were heads

of both, it is true, but the governments were more or less

independent (with a couple of exceptions, the army being one).

So the Emperor of Austria (well, this is a sort of nickname) was

also the King of Hungary. Hence, the K.- und K. Army (the

kaiserliche und königliche Armee--the Imperial and Royal

Army).

So this is the interesting Empire whose heir to the throne was

assassinated on June 28, 1914. And in helping start the First

World War by forcing this issue with the Serbians, the House of

Habsburg really started the process that would end its place at the

highest levels of European influence, apparently for good, in 1918.