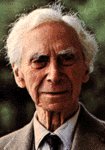

(BIOGRAPHY: Bertrand Russell was born into a liberal and aristocratic family

descended from a Prime Minister. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he

read mathematics. He later became devoted to the foundations of mathematics. From 1907 to

1910 he worked in collaboration with Alfred North Whitehead for ten to twelve hours a day

eight months a year on Principia Mathematica. During this period he also laid the

foundation of his life as a radical, active, liberal intellectual, beginning by standing

as a suffragist candidate for parliament. During the First World War he was imprisoned for

six months for publishing the statement that American soldiers would be employed as

strike-breakers in Britain, "an occupation to which they are accustomed when in their

own country". After the war, Russell visited Russia and lived for a period in China.

He opened and ran a school, but from 1938 to 1944 taught at a number of American

universities. He was however denied employment by the City University of New York, on the

grounds that his works were "lecherous, libidinous, lustful, venerous, erotomaniac,

aphrodisiac, irrelevant, narrow-minded, untruthful, and bereft of moral fiber". In

the late 40's Russell published his last important philosophical work, but by this time,

he was a world famous symbol of philosophy and its radical potential. He was awarded the

Nobel Prize for literature in 1950, and as the unmistakable patriarch of the liberal

academic world spent the rest of his life actively campaigning for nuclear disarmament.

(BIOGRAPHY: Bertrand Russell was born into a liberal and aristocratic family

descended from a Prime Minister. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he

read mathematics. He later became devoted to the foundations of mathematics. From 1907 to

1910 he worked in collaboration with Alfred North Whitehead for ten to twelve hours a day

eight months a year on Principia Mathematica. During this period he also laid the

foundation of his life as a radical, active, liberal intellectual, beginning by standing

as a suffragist candidate for parliament. During the First World War he was imprisoned for

six months for publishing the statement that American soldiers would be employed as

strike-breakers in Britain, "an occupation to which they are accustomed when in their

own country". After the war, Russell visited Russia and lived for a period in China.

He opened and ran a school, but from 1938 to 1944 taught at a number of American

universities. He was however denied employment by the City University of New York, on the

grounds that his works were "lecherous, libidinous, lustful, venerous, erotomaniac,

aphrodisiac, irrelevant, narrow-minded, untruthful, and bereft of moral fiber". In

the late 40's Russell published his last important philosophical work, but by this time,

he was a world famous symbol of philosophy and its radical potential. He was awarded the

Nobel Prize for literature in 1950, and as the unmistakable patriarch of the liberal

academic world spent the rest of his life actively campaigning for nuclear disarmament.

Appearance and Reality

Overview: Note the

similarities to Descartes; what within our present experience can we be certain of? That I

am sitting in a chair, looking at the sun, etc. But does my experience provide sufficient

warrant or proof for believing such things?

Consider the table: depending

upon the angle one has upon looking at it, and the way the light and shadows fall across

it, it will appear one way to one observer, another way to another. Since no two people

can see it from precisely the same point of view, and since the light falls on it

differently from different points of view, it will not look the same to anyone. But

if that is so, does it make any sense to say what the real shape (or color, or texture)

the table REALLY is?

a) If you respond "But

that is not how it looks to me", what reason can you give me for thinking that the

way you have described it is the "real" shape of the table, and not merely how

it "appears" to you?

b) Similarly with its color:

"When, in ordinary life, we speak of the colour of the table, we only mean the sort

of colour which it will seem to have to a normal spectator from an ordinary point of view

under usual conditions of light. But the other colours which appear under other conditions

have just as good a right to be considered real; and therefore, to avoid favoritism, we

are compelled to deny that, in itself, the table has any one particular color."[230]

c) Likewise with texture,

shape, and touch. In every case, Russell argues, our senses give us "not the truth

about the table itself, but only about the appearance of the table."[231]

CONCLUSION:

"Thus it becomes evident

that the real table, if there is one, is not the same as what we immediately experienced

by sight or touch or hearing. The real table, if there is one, is not immediately known to

us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known. Hence, two very

difficult questions at once arise; namely, (1) Is there a real table at all? (2) If so,

what sort of object can it be?

What do you think?