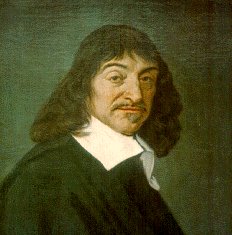

BIOGRAPHY: French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist.

His philosophy is called Cartesianism (from Cartesius, the Latin form of his name). Born

in La Haye, France, and trained at the Jesuit College at La Flèche, Descartes remained a

Catholic throughout his life, but soon became dissatisfied with scholasticism. While

serving in the Bavarian army in 1619, he conceived it to be his task to refound human

knowledge on a basis secure from skepticism. He expounded the major features of his

project in his most famous work, the Meditationes de primaphilosophia (1641, Meditations

of First Philosophy). He began his enquiry by claiming that one can doubt all one's sense

experiences, even the deliverances of reason, but that one cannot doubt one's own

existence as a thinking being: cogito, ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am").

From this basis he argued that God must exist and cannot be a deceiver; therefore, his

beliefs based on ordinary sense experience are correct. He also argued that mind and body

are distinct substances, believing that this dualism made possible human freedom and

immortality. His Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la

vérité dans les sciences (1637 Discouse on the Method for Rightly Conducting One's

Reason and Searching for Truth in the Sciences) contained appendices in which he virtually

founded co-ordinate or analytic geometry, and made major contributions to optics. In 1649

he moved to Stockholm to teach Queen Christina of Sweden.

BIOGRAPHY: French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist.

His philosophy is called Cartesianism (from Cartesius, the Latin form of his name). Born

in La Haye, France, and trained at the Jesuit College at La Flèche, Descartes remained a

Catholic throughout his life, but soon became dissatisfied with scholasticism. While

serving in the Bavarian army in 1619, he conceived it to be his task to refound human

knowledge on a basis secure from skepticism. He expounded the major features of his

project in his most famous work, the Meditationes de primaphilosophia (1641, Meditations

of First Philosophy). He began his enquiry by claiming that one can doubt all one's sense

experiences, even the deliverances of reason, but that one cannot doubt one's own

existence as a thinking being: cogito, ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am").

From this basis he argued that God must exist and cannot be a deceiver; therefore, his

beliefs based on ordinary sense experience are correct. He also argued that mind and body

are distinct substances, believing that this dualism made possible human freedom and

immortality. His Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la

vérité dans les sciences (1637 Discouse on the Method for Rightly Conducting One's

Reason and Searching for Truth in the Sciences) contained appendices in which he virtually

founded co-ordinate or analytic geometry, and made major contributions to optics. In 1649

he moved to Stockholm to teach Queen Christina of Sweden.

Perhaps the most popular view

about the relationship between mind and body is DUALISM -- the belief that mind and body

are two separate entities, and that the mind is essentially non-physical (and hence is

beyond the reach of the physical sciences). Descartes is most associated (in modern times)

with this view. Dualism comes in a variety of forms, which are distinguished by how they

describe the relationship between the mind and body. Here are but some of the

possibilities:

INTERACTIONISM: An

interactionist believes just what the name implies -- that mind and body interact. Mental

activities (believing, desiring, intending, hoping, etc.) can therefore cause changes in

the body (i.e. my belief that I am in danger can cause me to

sweat profusely, to run away from the perceived cause of that danger, etc.), and physical

changes can likewise cause mental events to occur (stubbing my toe causes pain,etc.) The

challenge for this view is to explain how a non-physical thing (the mind) can bring about

a change in a physical thing (the body), and vice versa.

EPIPHENOMENALISM: Here

mind and body are separate, but the mind is created or caused by the brain.

("Epi-" is a prefix from the Greek that means "above" -- hence to

characterize mental activity as epiphenomena is to claim that such activity is above or

outside of physical phenomena.) This is an odd sounding view, but it has two appealing

traits -- first, it allows us to hold onto our belief that we have mental states which are

more than simply physical properties of the brain; and second, it seems less

"spooky" than interactionism because it makes the physical (the brain) the cause

of the mental (as opposed to being a wholly separate entity). There are two types of

epiphenomenalists -- those who are interactionists (who believe that mental properties,

though caused by the brain, can affect the brain, and vice versa), and those who are not

(who claim that the brain can affect the mind, but the mind cannot affect the brain). The

problem for the interactionist epiphenomenalist is the same as for the plain-old

interactionist -- explaining how mind and brain interact. The non-interaction version of

epiphenomalism inherits this problem as well, and a different one. It seems clear that our

mental life does bring about physical changes (as our earlier example of perceived danger

suggests). The non-interaction epiphenomenalist denies this...and that's a problem.

PARALLELISM: The

difficulties of explaining the interaction between mental and physical led some to posit

parallelism, the view that mind and body do not interact at all, but simply run in

parallel. Imagine two clocks side by side, each displaying the exact same time. Though in

perfect synchronicity, neither affects the other. Thanks to God, our mental life and

physical life mirror one another perfectly, but only because they were designed this way,

and not because they interact. Hence on this view, when I stub my toe, I get the mental

sensation of pain NOT because the physical act of stubbing my toe CAUSED the pain, but

because my mental life was designed to have an experience of pain at that very moment. All

works in pre-established harmony. The advantage of this view is that it allows one to hold

onto the notion that mind and body are different, without needing to explain how they

interact. The challenge for this view is that it requires not only a belief in God, but a

belief in predestination (that one's mental and physical life are already fully

determined) which raises other problems with the notion of freedom of the will, etc.

Descartes offers 2 arguments that the mind and body are separate.

PRINT OUT THIS PAGE AND BRING IT TO CLASS. I will expect you (1) to explain arguments (A)

and (B), (2) to suggest possible criticisms for these arguments, and finally, to come with

a WRITTEN response to part (C).

(A) The argument from

divisibility (first paragraph, p. 77)

1. My body is divisible into parts.

2. My mind is not divisible into parts.

3. (IMPLIED PREMISE: Two objects (A and B)

are identical only if the properties of A are properties of B.

-------------------------

4. Therefore, my mind and body are not

identical.

(B) Animal and human nature

(first full paragraph, p. 79)

1. Animals (especially higher mammals)

possess almost all the same organs and physical structure that humans do.

2. Animals cannot think; humans can.

-------------------------

3. Therefore, humans must possess some

faculty animals do not possess.

4. But given (1), that faculty cannot be

physical (or based in physiology).

-------------

5. Therefore, humans possess a non-physical

mind.

(C). Explain the two tests

(p. 190) which Descartes believes we can use to distinguish real persons from machines (or

automatons) that only resemble persons.